Demystifying Deep Learning: Part 1

What is a neural network?

July 28, 2018

4 min read

Introduction

In this series of blog posts I aim to demystify the main types of neural networks, and delve into the maths behind these deep learning algorithms. The aim is to reason from first principles - to do this each blog post will cover the following 3 aspects:

- Intuition: get an overall feel for why this works

- Maths: delve into the theoretical side and the maths that makes it work

- Code: consolidate learning by applying the maths using a motivating example.

Terminology

First, let’s try to define what machine learning even is. Machine learning is the ability of computers to learn from data without being explicitly programmed. However, unlike the portrayal in the media, most machine learning algorithms are highly specialised, so are limited to performing few tasks very well - for example the AI used to detect cats and dogs in images can’t then play chess. The AI world domination scenario is some way off, at least not in the forseeable future, not until we can create some generalised form of artificial intelligence.

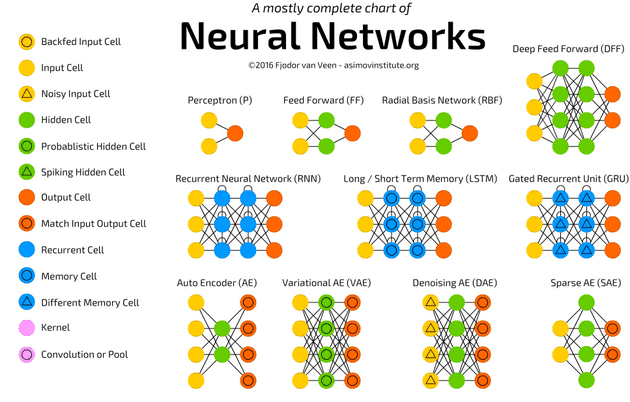

Deep Learning is a subset of machine learning algorithms encompassing artificial neural networks, whose architectures are loosely inspired by the human brain. Deep learning is often used interchangeably with neural networks when referring to this field.

We also interchangeably use the term model when referring to a machine learning algorithm - i.e. a model of the relationship between the inputs and outputs.

Types of machine learning

More generally, machine learning algorithms typically fall into 3 classes:

Supervised Learning: This is where we provide the algorithm with the input features and also the correct output labels. Think of the algorithm as a student being asked to calculate the answer based on the input, whilst we act as the teacher, providing it with the right answer (label).

Unsupervised Learning: Suppose instead we just gave the algorithm the data without any labels. This is unsupervised learning - we are not telling the algorithm what is right or wrong - instead we let it make sense of the data and find structure. One example is a clustering algorithm which groups similar items in the dataset together.

Reinforcement Learning: This is where, at each timestep, the algorithm chooses one of a set of actions and then receives a reward based on whether the action was good or not (just like how you might give a dog a treat for performing a trick). The algorithm aims to maximise the total reward.

We will initially look at supervised learning algorithms, and only later look at the other two classes of machine learning. The vast majority of problems where we apply machine learning tend to be supervised learning problems.

Datasets

One area that is especially important in machine learning is the data. Handling data properly is thus of paramount importance, and one of the pre-processing steps is to split our dataset into 3 datasets:

- Training

- Validation/Dev

- Test

Why do we split the data?

The training set is the data the model “sees” when learning (i.e. in supervised learning it gets both the labels and the input features).

When training the model, we want to tune the hyperparameters - the “finetuning knobs” of the model to get the best performance. However, when evaluating the performance on the training set we don’t know if the model performed better because we tuned these hyperparameters correctly or because it had already seen the examples before and “memorised” them. To be certain, we want to validate this on a dataset the model hasn’t seen - this is the validation set.

Having done all this, we want to get a benchmark on how well this model has done, to compare it to other models. We can’t use the training set, because it may have memorised the examples. Nor can we use the validation set, because we have seen the validation set and chosen the values of the hyperparameters that do best on it. We want to know how well the model does generally, not just on this specific dataset, so we need to have an untouched dataset (by both us and the model) that we look at once we’ve finished tuning - this is the test set.

We will look into preprocessing the data in more detail in later blog posts. The key takeaway is that we do not want an inflated view of our model - we want an unbiased estimate of how well it can generalise to unseen data.

Types of Problem:

Finally, there are two main problems we look at in supervised learning - depending on the type of the output we are trying to predict.

Regression: This is where the output prediction is real-valued and continuous, i.e it can take all values within a range - house prices can range from £100,000 to £500,000 for example.

Classification: This is where the output is discrete - it can only take on one of a few categories - like for example types of objects in an image - e.g cats, dogs, birds etc.

NB: there is a subtlety. If we restricted the housing prices to “buckets” e.g. £0-10,000; £10,001-£50,000 etc. then this would actually turn this regression problem into a classification problem since there are a fixed number of discrete buckets.

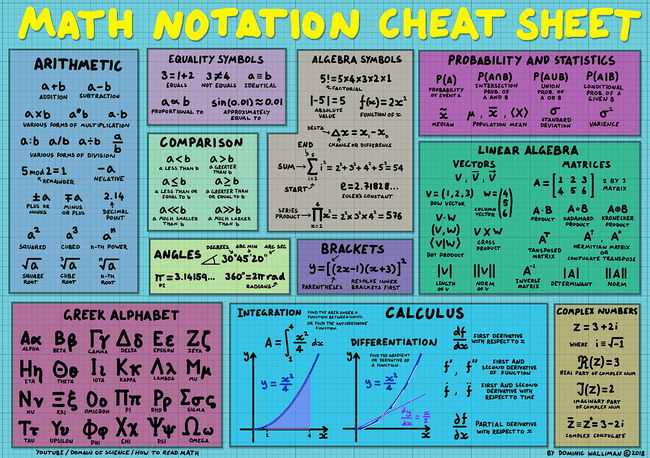

Maths Notation

Often with maths equations, the notation can make the maths seem intimidating or confusing. This cheatsheet gives a quick breakdown of the notation I’m using (along with some additional core maths notation). It’s worth taking a moment to go over this and making sure you’re comfortable - if you need a refresher Khan Academy is an excellent resource.

Summary

Woah! That was a lot of terminology. It’s important to have these terms in the back of your mind for later posts, since these terms are commonplace in most machine learning blog posts and tutorials.

In the next lession we will look at our first two machine learning algorithms, linear and logistic regression!