A handy guide to Dune - the BEST ReasonML/OCaml build system out there

January 17, 2020

5 min read

Last updated: February 04, 2020

Why have a build system?

When working on a larger OCaml project, you’ll eventually end up working on programs spread across multiple files. In OCaml, each file foo.ml can be used as a module Foo in other files, with its interface exposed in a foo.mli file. More detail in Real World OCaml. But this introduces a dependency: you need to link the compiled foo.ml file with any files that use the module Foo.

Trying to keep track of these dependencies when compiling these files manually becomes a pain as your project scales. Build systems like Dune take in build rules and automate this process for you.

I’m going to spend this post explaining the ins and out of Dune and also get into some of the really cool ways it interoperates with the rest of the OCaml ecosystem. In the template repo, I’ve also included a ReasonML example - Dune works great with both OCaml and ReasonML.

For #OCaml and @reasonml, Dune is the ONLY build system you should be using!

JUST GIVE ME THE CODE!

The template repo contains the examples mentioned in the blog post. Fork it to get up and running with Dune!

Setting up your project

You can install dune using OCaml’s package manager opam. Simply run opam install dune.

For your project, in the project’s root directory, you’ll also need a opam file. (For JavaScript programmers, an opam file is similar to a package.json file). More info about opam files.

Dune is a composable build system. Each directory contains a dune file (note the lack of file extension) specifying how to build the files in that directory, and Dune composes them when building the project.

Alongside the dune files, projects contain a dune-project file in the root directory. In this file, you specify the name of the project, but also the version of Dune you’re using (we’re using version 2.0 here). This means that even if future versions of dune are not backwards-compatible, it won’t affect our project.

Dune’s build file syntax consists of stanzas, which are bracketed s-expressions e.g. (lang dune 2.0) and (name hello_world).

So your dune-project file is:

(lang dune 2.0)(name hello_world)

Dune files

dune files are where we really specify all the build configuration options. Remember, at most one dune file per directory.

There are three different types of stanza we can write in a dune file:

Executable

(executable(name main)<options>)

This creates a binary that we can execute using dune exec main.exe (note file ending is .exe regardless of whether on Windows or not).

Test

(test(name foo)<options>)

or alternatively, if there are multiple tests in that directory:

(tests(names foo bar baz)<options>)

I’ll talk more about writing tests in a follow-up post where we’ll look at OCaml testing frameworks. For this post on Dune, the key takeaway is that dune runtest will find and run all the tests specified by these test stanzas.

Library

(library(name lib)<options>)

This creates an OCaml library lib, which we can build using the command dune build. We can refer to module Foo in that library as Lib.Foo. You can think of Libas a module that contains all the modules in the same directory as the dune file.

If however, we have a module with the same name as the library (here Lib), the library only consists of this module (it ignores the other modules in the directory), and we refer to this module as Lib not Lib.Lib.

Configuring Build Options

Within stanzas, we can list additional options for our build. Here are a few useful commands in Q & A format:

How do I create a public library?

Add the (public_name <name>) stanza. Note however, that there must be a opam package file of the same name in the root of your project.

E.g. if we have

(library(name foo)(public_name foo))

then we must have a corresponding foo.opam file in the project’s root directory. Note however, that if your library is public, then all libraries that are dependencies must also be public.

How do I use other OCaml libraries?

Add the (libraries <names>) stanza to your dune file.

E.g. an executable that wants to use the Core and Fmt libraries:

(executable(name main)(libraries core fmt))

How do I access modules in a different directory?

Option 1: Create a library stanza that includes those modules. Then use the (libraries <names>) approach detailed in the previous question.

Option 2:

If the modules are in a subdirectory, then you can use the (include_subdirs unqualified) stanza.

(include_subdirs unqualified)(executable(name main)...)

Unqualified means Dune treats the subdirectory files as if they were in the parent directory. This does however mean that you can’t have any dune files in the subdirectories, since a module can’t be part of both this stanza and the subdirectories’ stanzas.

What if I want to have multiple stanzas in the same dune file?

As mentioned, a module can’t be part of multiple stanzas. By default Dune implicitly includes all the modules in a directory in the single library/executable/test stanza in the dune file. With multiple stanzas, we need to be explicit about which modules each stanza contains - so each stanza must include the (modules <names>) option.

You might want this if you have a library and an executable in the same directory:

(library(name foo)(modules bar baz))(executable(name main)(modules main)(libraries foo))

Dune is now happy with this as modules bar, baz and main are each only included in one stanza.

How do I preprocess files with PPX?

PPX are syntactic extensions to OCaml, which need to be pre-processed to be converted to valid OCaml syntax, using the stanza (preprocess (pps <ppx extensions>)). E.g. if you wanted to use the two PPX extensions: PPX Jane and Bisect PPX, you would use:

(library(name foo)(preprocess(pps ppx_jane bisect_ppx)))

An aside, Bisect PPX is used for computing test coverage - this is covered in the next post on testing in OCaml.

What if I want to lint my OCaml files?

There aren’t many linters for OCaml out there right now - your best bet is PPX JS Style. To use this you’d add the command

(lint(pps ppx_js_style -annotated-ignores -styler -pretty -dated-deprecation)))

Breaking this down, the pps is used since we’re dealing with PPX extensions, and -__ are flags are passed to ppx_js_style.

Dune commands

Alright, so now we’ve specified build files, let’s talk about the dune commands.

Building (only specific directories)

dune build builds all the files in the project, whilst dune build <dir> builds only the files in the given directory and its subdirectories. Build files are stored in the _build/ directory.

Executables

We have dune build ___.exe to build a given executable, and dune exec __.exe to build and run the given executable.

Tests

For tests, we mentioned we can run dune runtest to run all tests in the project and we have dune runtest <dir> to run only the tests in the given directory and its subdirectories.

Formatting and Promotion

dune build @fmt runs an autoformatter over the files when it builds the files: for OCaml this is OCamlformat, for Reason this is Refmt. To then update the source files with the content of the formatted build files, we can run dune promote.

We can do this in one command: dune build @fmt --auto-promote. (A must-have command for a pre-commit hook!)

Autogeneration of documentation

Dune is also tightly knit with Odoc, a tool that autogenerates HTML documentation for a OCaml / Reason project.

Running dune build @doc generates HTML documentation for all public libraries in the project - the docs can be seen in _build/default/_doc/_html/. The root index.html file consists of a list of the opam packages corresponding to the public libraries, and you can then follow the links to see documentation for individual modules.

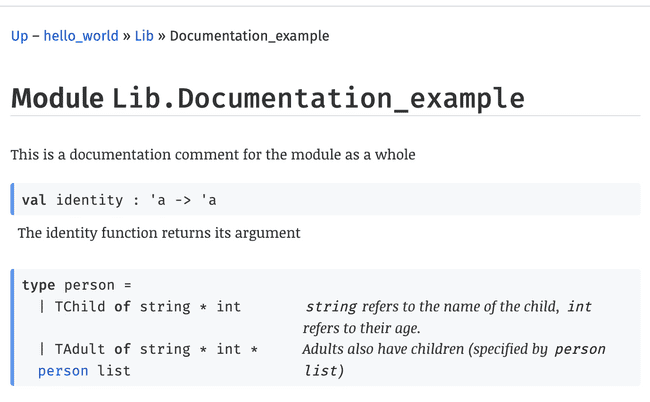

Documentation is generated from the comments in the .mli files for a module e.g. for module Foo, you can use (** *) to annotate a function or type.

(** This is a documentation comment for the module as a whole *)(** The identity function returns its argument *)val identity : 'a -> 'atype person =|TChild of string * int (** [string] refers to the name of the child, [int] refers to their age. *)| TAdult of string * int * person list (** Adults also have children (specified by [person list])*)

An example of this can be seen at https://ocamltest.mukulrathi.com/ - which is the HTML documentation for the template repo that goes with this blog post.

For private libraries, you can run dune build @doc-private to generate HTML documentations, however you won’t be able to navigate to the library from the list on the root index.html file since there’s no corresponding opam package for the library.

Dune’s integration with OCamlformat, Odoc, Merlin and the rest of the OCaml ecosystem is one of its key USPs.

Linting

Remember that (lint ) stanza we mentioned? The command dune build @lint runs the linter specified in that stanza.

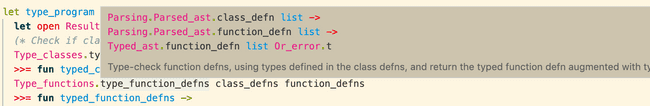

Bonus: IDE Integration

Dune also generates .merlin files for the directories. Merlin is a service that integrates with editors to provide autocompletion and other IDE features. For VSCode, check out the OCaml and Reason IDE extension. It makes programming in OCaml a joy - if you’re not sure of the type signature of a function, just hover over it!

Wrap Up

There are a lot more configuration options for Dune in the Dune docs - you can even specify your own custom build rules should you so desire. The best way to get to grips with Dune is to use it! So be sure to fork the template repo that goes with this blog post.

If you have any questions or know of any other cool tips and tricks with Dune, please tweet it my way!